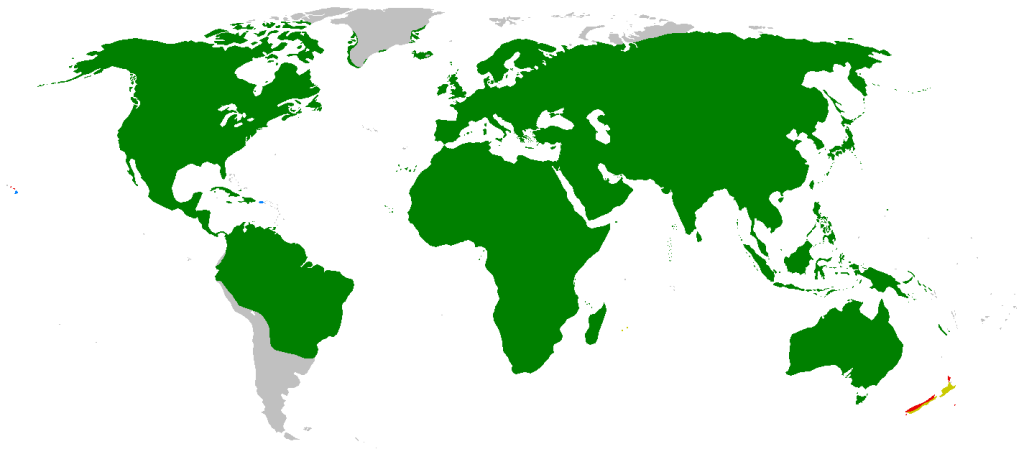

According to Wikipedia, there are 133 species of corvids. Corvidae are part of the larger order known as Passerines. Passerines are known as songbirds (yes, corvids sing, even if we don’t always like the sound) but also as perching birds. We can all agree that crows perch! Anyway, the corvids include crows and ravens, but also rooks, jackdaws, jays, magpies, treepies, choughs and nutcrackers. They are found on every continent except for Antarctica, and they have made it to many far-flung islands, such as Hawaii and New Caledonia.

How did they get to so many different places? Corvids are not powerful migrators, although some do it. They can’t cross the ocean the way some birds can. However, the planet has changed considerably with time. The continents used to be closer together. The corvid family has been around 17 million years, so that may have helped. And, during ice ages, seas were much lower, exposing far more land. Note I am just speculating, but these things seem reasonable.

Corvids, especially ravens and crows, are considered to be some of the smartest birds. Some of them recognize themselves in mirrors, and some of them make tools. Mirrors and tools were the vain ways that humans used to claim superior intelligence to all other species. And yes, humans are smart; we have a new telescope out in space, but just imagine building a nest with a beak and a pair of talons! And you can’t use both feet at the same time, not unless you’re flying.

Anyway, here’s a New Caledonian crow in the wild using a tool. Not one of the New Caledonian crows in captivity who have proved their intelligence by solving all sorts of problems (but they’re in captivity, so they may be less intelligent than their wild relatives).

The largest corvids are ravens, weighing over 1400 grams, or, in the Imperial system, more than 3 pounds. The two types of ravens that meet this are the Common Raven and the Thick-Billed Raven.

The smallest corvid is the Dwarf Jay. It weighs about 41 grams, and if you want that in pounds, that’s less than one-tenth of a pound! It is about 8-9 inches in length. It lives in a part of Mexico, and due to habitat loss, it is in the “Near Threatened” category. It resembles many other jays. Here’s a picture:

According to experts, the Alpine chough is the highest flyer in the corvid cousins, nesting in the Alps and the Himalayas. I have spent loads of time in Switzerland and I often see huge groups foraging at lower altitudes in winter. Alpine choughs are pretty hardy; I also saw one take a very cold water bath – a plastic basin I use for gathering weeds had filled up with snow – as soon as it melted, an Alpine chough jumped in, while the other species only used that basin to quench their thirst.

Corvids are especially susceptible to the West Nile virus, which is carried by mosquitos. Humans also get this disease, but we don’t die at the terrible rates that afflict corvids. American crows, blue jays and yellow-billed magpies died at rates of up to 50%, which is much higher than the rates for other birds.

Many corvid species are adapting to humans and our changes to the environment, but some are having a difficult time of it. The Hawaiian crow now only exists in captivity; due to habitat loss, it is “extinct in the wild”. Others are doing much better, despite the follies of humans. Have you ever heard of the cane toads and how they were brought to Australia? The idea was that cane toads would eat pests that eat crops.

To be fair, cane toads do eat pests that eat sugarcane pests in other countries (which is why they’re called cane toads, sugarcane). However, the cane toads did not eat Aussie pests, and they turned into pests themselves. On top of that, the skin of the adults is so toxic that most predators died when they ate them.

The Australian crows were not to be outsmarted. They figured out how to eat this new source of food, by flipping the cane toad on to its back, holding it down with a talon, then eating the soft underbelly.

Not the nicest way for the cane toads to die, but it shows the adaptability of these brilliant birds.

Hope everyone is well in these strange times, and please fly by again to read a few random feathers I have arranged for you.

Victoria Grossack is the author of the Crow Nickels, of which two volumes are available: Hunters of the Feather and Scavengers of Mind. They are about Sol, a thinker-linker crow who has a quest to save the Great Flock from climate change. “Try, and again try, till you win or till you die.” Junkyard Abner, Hunters of the Feather